Under current constitutional rules, the maps are only in effect for four years if they are passed without minority support. That’s why the maps are only in effect from 2022-2026.

Unless another proposal is adopted, that means Ohio will use a system that has drawn criticism from officials of both parties and has produced various maps that the Ohio Supreme Court deemed unconstitutional based on the redistricting system’s own standards.

The Ohio Constitution requires that the state’s legislative and congressional districts “correspond closely” to Ohioans’ voting patterns.

Here’s how that works: In statewide partisan elections over the past 10 years, Ohioans have voted for the GOP candidate 55.1% of the time on average. Which means that if new maps were drawn tomorrow, close to 55.1% of Ohio House, Ohio Senate, and U.S. House districts should favor Republicans, while the remainder should favor Democrats.

Moon Duchin, a math professor at Cornell University who analyzes redistricting, told this outlet that Ohio’s political geography, along with the current system’s array of map drawing rules, makes it particularly difficult to achieve the target proportionality.

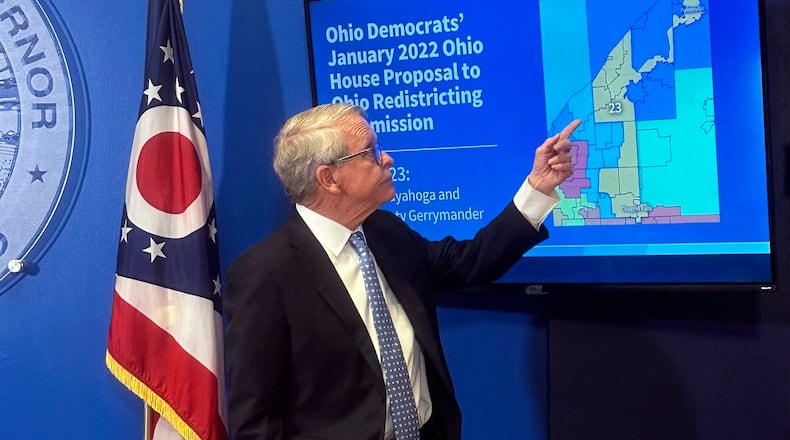

A primary way to achieve proportionality in Ohio today is by strategically assessing Democratic party strongholds, dividing it into smaller-but-still-potent parts and intentionally stretching a district to ensure that those stronghold chunks reach into traditionally Republican areas.

But in Ohio, Democratic strongholds are increasingly contained within the state’s most populous counties and anchored in the state’s most populous cities. Democrats, who over a decade ago could carry northern lake shore counties or eastern Appalachian counties, now only regularly carry Athens County, home to Ohio University, outside of the state’s six most populous counties.

“I’ve looked at every state and Ohio is one of the most extreme in terms of just the geography or where the cities are, which ones are at the edge of the state, kind of how the population is distributed,” Duchin said. “Just that, on one hand, shakes out to be quite favorable to Republicans.”

This shift, combined with the fact that three of Ohio’s Democratic strongholds lie on the state’s fringes (Cleveland and Toledo’s Democratic base cannot be stretched northward and Cincinnati cannot be stretched southward) leaves map drawers with limited options to actually create enough Democratic districts to adhere to proportionality.

Even more restrictions baked into the Constitution exacerbate the conundrum.

All districts must be drawn around eligible incumbents’ hometowns, creating 99 anchor points in the Ohio House map, 33 anchor points in the Ohio Senate map, and 15 anchor points in the U.S. House map; counties cannot be split more than once; communities of interest must be kept intact — all factors reducing mapmakers’ options.

As a result, Ohio’s maps (drawn and approved by a Republican-dominated politician panel) have often fallen short of the proportionality standard since it was enshrined into the Constitution. Even in the current maps used for Ohio elections, the Ohio House map favors Republicans 63% of the time; the Ohio Senate map favors Republicans 69% of the time; and the Ohio U.S. House map favors Republicans 67% of the time, despite Republicans usually receiving vote shares in the mid-50s.

However, Duchin pushed back on the notion that compact districts and a proportional district map in Ohio are impossible to marry. “Could you draw a proportional map in Ohio even while following all the rules? And the answer is yes, you can,” she said. “You can if you try.”

For more stories like this, sign up for our Ohio Politics newsletter. It’s free, curated, and delivered straight to your inbox every Thursday evening.

Avery Kreemer can be reached at 614-981-1422, on X, via email, or you can drop him a comment/tip with the survey below.

About the Author